A. W. Woods: Christmas 1916

PART SEVEN IN A SERIES ON SAINT MARGARET’S AND THE GREAT WAR

A Christmas in the Trenches

Lieut.-Col. A. W. Woods, Written from the trenches, January 1, 1916

Christmas, what does it mean to us? “Peace on earth, Good Will towards men.” Could one honestly repeat that message to the poor fellows wallowing in the mud in the Douve Valley in front of Messines? Could one honestly wish it to the man being carried out of the trench on a stretcher with mutilated body, soaking wet, and plastered with mud? Can one write it to the anxious mother and father and sweetheart who are waiting with an awful dread in their hearts for the announcement of the bulletin board, for news of their absent ones? Can we wish it for the thousands of bereft parents the world over who are suffering the consequences of this awful carnage brought on by a nation gone mad? Yes, it is difficult, but it is, after all, the only message that will meet such conditions; it is the one offset for a world that has taken leave of its senses. Ours would be a sad world indeed in any set of man-created conditions could render null and void the Divine message of love.

Let me describe my first Christmas in the trenches, in front of Messines. Two battalions of the Second Brigade were in the front with detachments from the two remaining battalions manning the forts on Hill 63 and in order to take advantage of the friendly darkness, I attended a number of services, the first one to be held at battalion battle Headquarters (at one o’clock, a.m.),

which was about 250 yards from the front line. A couple of days before, a plum pudding arrived from Ireland from a friend, and and a box of cigars from Winnipeg, and I thought that I could back up my Christmas wishes by offering these ever welcoming luxuries. The night was pitch dark, no light save the intermittent light from the flares. A road led from the top of the hill down to the centre of our position, called the Messines Road, and was commanded by the Boche machine guns. But by keeping close to the trees which grew on either side, one was reasonably safe, and it was much better than going across country in the dark. So, shouldering my haversack containing my padre outfit, the plum pudding and box of cigars, I started off for my midnight Christmas Eve service. And almost the first question that arose in my mind was, “Can I speak the words of Goodwill to those boys whose duty is to kill?” I wondered. Looking ahead one could see the heavens lighted up with flashes from the opposing forces who were watching and listening, watching and listening for an opportunity to hurl death at each other. “Peace on earth, Goodwill to men,” and every word punctuated with a rife shot and sung to the tune of the continuous rat-tat of the machine gun. But still it is the eve of the anniversary of the Prince of Peace. Occupied with these thoughts, I unconsciously approached a barrier across the road, and a voice rang out, “Halt, who are you?” I did not reply immediately, when out shot a bayonet, and the question was repeated in language that offered no delay for the answer. “Peace on earth, Goodwill to men.” I was passed through after a little chat and a cigar. A few yards further, and zip, zip, followed by the staccato report of the machine gun, and I ducked and whispered, “Peace on earth.”

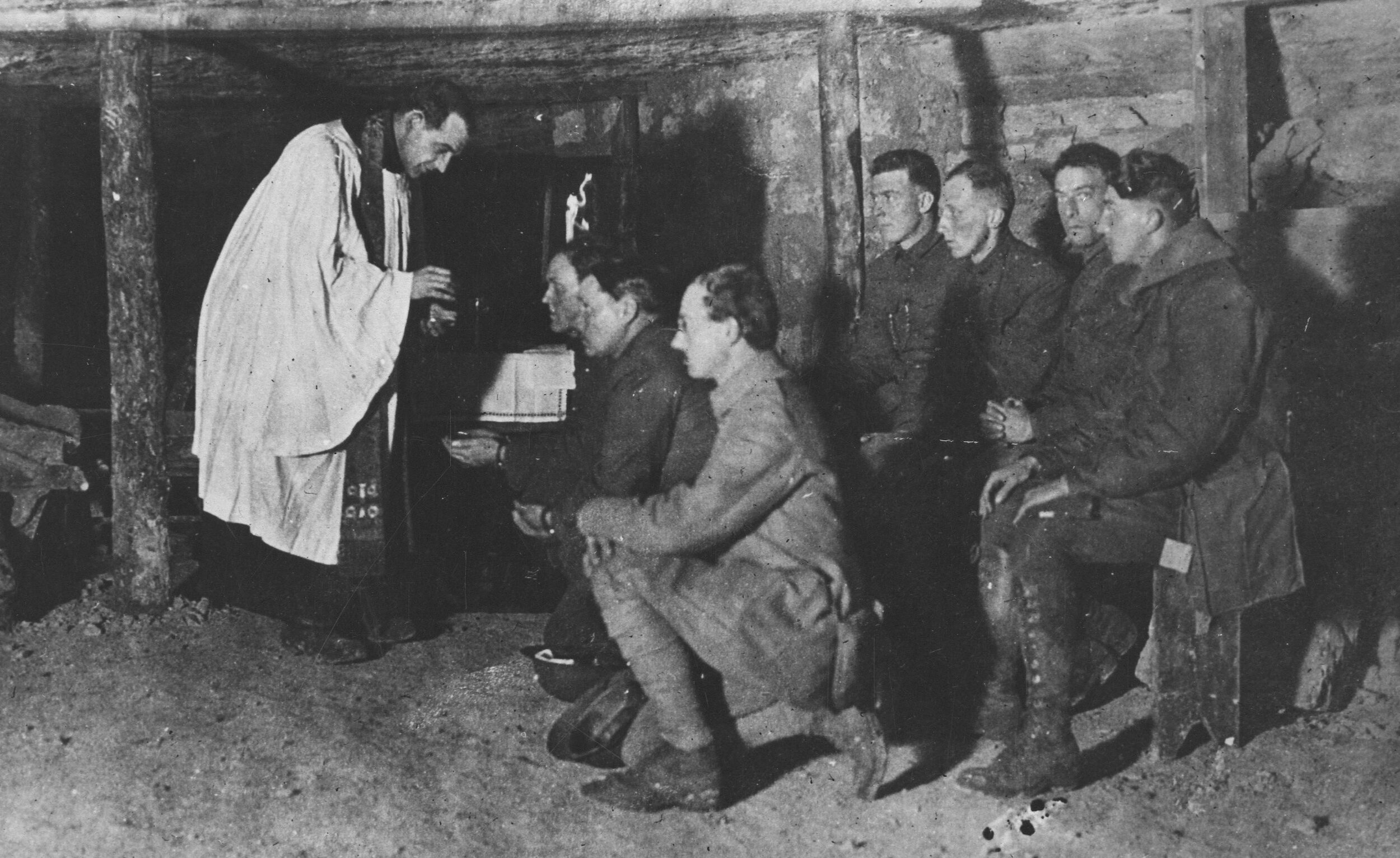

A little further on a faint light glimmered through a crack in a dugout in the side of the trench and two muddy feet protruded from under the rubber sheet that served as a door; two men were sound asleep there. I lifted the sheet and said in a low voice, “A Merry Christmas, boys,” and expected a bully beef tin in reply. Instead, up popped a head and with a grin, replied “The same to you, padre.” I thought it worth the plum pudding; God bless those boys. I passed on and reached our headquarters, and there we had our Communion service. Two hundred yards away the work of killing was going on, while in that little sand-bagged room were the evidences of that other Spirit, the Spirit of Love, Peace and Forgiveness, and the promise that out of all this turmoil would emerge a brighter and better world. No parson could have wished for a more appreciative congregation than those mudstained, khaki-clad men that knelt around that rude altar the first hour of that Christmas morning. True, there was no organ accompaniment, no altar banked with flowers, no choir to sing the Christmas anthem; but the Peace of the Prince of Peace dwelt in the hearts of that little congregation that knelt there, besmeared with mud; a peace and comfort and strength, that only those who possess it know; a peace mysterious, but to them very, very real. Thus was my first Christmas service held, and so on until 3 p.m. on Christmas afternoon little groups of men gathered in the dugout and hut as opportunity offered, to partake of Christ’s Christmas Feast. And so passed the first Christmas in the trenches in France.

It would be a mistake to say that none of us allowed our thoughts to dwell on other Christmas gatherings of much happier days. In spite of trying not to do so for obvious reasons, our thoughts would ever and anon fly off to those sacred spots on God’s earth which holds for us men all that we love on earth, where wife and child are watching and praying for the safety and return of him to whom they have been given. We ask the question, “Will it be ours to spend another Christmas playing this hell-game; or will we, like many others, be numbered among those who have given their lives to make a Roman holiday for a modern Nero? May we look for the blessings of peace as one of the gifts of this New Year? God alone knows. However, each day brings with it a fresh determination to see the horrible Drama to the end, whatever that may be for the individual.