A. W. Woods at the Second Battle of Ypres

St Margaret’s has a unique relationship to the Canadian chaplaincy in the First World War, in that our first two rectors, Albert William Woods and George Anderson Wells, were among the first Canadian chaplains to arrive in Europe, and were witness to the horror of the first use of poison gas in warfare, at the Second Battle of Ypres. For the second half of the war, Woods and Wells were two of the four senior chaplains to the Canadian Forces in Europe, so that between them, fully half of the Canadian soldiers in combat were under their spiritual charge.

The Second Battle of Ypres was one of the early indications that the First World War would be a horror unlike the world had yet seen or imagined. And the chaplain to those first casualties of this new kind of horror, who was there with them, who heavily felt the responsibility for their spiritual welfare and comfort, was the founding rector of St Margaret’s, A. W. Woods. Many of the casualties were evacuated to the 2nd Canadian Stationary Hospital, which had been set up in a grand hotel in the beach town of Le Touquet, where the sole chaplain was one George Anderson Wells, who after the war would be appointed the second rector of Saint Margaret’s. He later wrote, “We had hardly recovered from our strenuous labours with casualties from the first Battle of Ypres, when we had to undertake the same heartbreaking task for those of the second Battle of Ypres. This time, however, there was a big difference. In the first battle we had dealt with practically all English and Scottish troops; in the second they were nearly all Canadian. And now there was a new kind of casualty. For the first time in warfare, a deadly, poisonous gas was used, to the surprise and horror of everyone. No one expected such a thing, and no one was prepared for it.”

What follows is an excerpt from a sermon preached at the evening service of Nov 15, 2020. - GM

A. W. Woods enlisted as soon as war was declared in August 1914, and by February 1915 he was in France, padre to the 2nd Brigade of the Canadian Division. In April, the Canadians were moved to the Ypres Salient. The Ypres salient was a little piece of Allied-controlled territory in Belgium. It was separated from the rest of the Allied-controlled territory by a canal that runs North-South past the city of Ypres. The Ypres salient - this piece of territory - bulged 4 or 5 miles into German-controlled territory, leaving it bordering enemy lines to the North and East and South. The salient was like a little island, with a canal on one side and the enemy on the other three. The French held the trench line along the north side of the salient, the British along the south, and the Canadians were brought in to hold the east side. On the other side of the canal, at least at this point in the war, was relatively safe: that’s where troops would go for relief from the front, and that’s where the Generals had their headquarters. The salient was prone to being shelled at any time.

About a week after the Canadians got there, the German forces made a major push to try to take the salient, and this push is known as the Second Battle of Ypres. On April 22, the German forces unleashed chlorine gas against the French troops holding the north side of the salient. This was the first use of chlorine gas in war. The gas stung the eyes and mouth, debilitating troops and causing panic. But it also triggered a reaction in the lungs that caused them to fill up with fluid, so that in the most serious cases it was fatal, causing men to effectively drown. The French line collapsed and German troops flooded into the salient, making their way West and South through the forest the soldiers called Kitchener’s Wood. If they pushed far enough, they would have been able to cut off the troops in the salient, the most exposed of whom were the Canadians on the east side. The two brigade commanders in the salient called on their battalions that were in reserve to move into Kitchener’s Wood and hold off the advance of the German troops. This situation held for two days of intense fighting with heavy losses. Then early on the 24th, the German forces unleashed a second chlorine gas attack, this time landing squarely on the four Canadians battalions holding the east side of the salient. One of the four battalions was the Winnipeg Rifles (the 8th Battalion), of which A. W. Woods was the chaplain, and the battalion included at least one other St Margaret’s parishioner, Reginald Minchinton, who fought in the battle, suffered from the gas attack, and would die two years later, just a few kilometers to the east, at Passchendaele.

Now all of the Canadian battalions were engaged in intense fighting and had virtually no reinforcement or support from the British or French, until on the 25, after four straight days of fighting, British troops were sent to relieve the Canadians. The losses to the Canadians in Second Ypres were staggering. Between death, injury, and captivity, the Canadian Division was almost cut in half. I haven’t dwelt on the horror of the scene, but there was horror in every direction. The gas was everywhere. Men were gasping and drowning. Mines were exploding, leaving craters 20 feet wide. One soldier spoke of seeing a comrade burning alive. Another told of German troops bayoneting the injured in the trenches. Sergeant William Miller wrote, “Imagine Hell in its worst form. You may have a slight idea what it was like.” The Canadians had been in the Salient 17 days, the final four of which had seen this continuous fighting. John McCrae called it “Seventeen days of Hades.” One of the padres, Canon Frederick Scott wrote, “On any grim monument raised to the Demon of War, the sole word “YPRES” would be a sufficient and fitting description.” For those four days in April 1915, the Yser Canal, was as a kind of River Styx. It was the boundary between the Land of the Living, and Hades. To the west of the canal, in the Land of the Living: the headquarters of the generals, towns still functioning as towns, relative peace. The army command structure was of absolutely no use to the men in the Salient; General Alderson might as well have been back in England for all the help he was. To the east of the canal, in the salient: the civilians had fled; a total absence of higher command; a chaos of shelling, rifle fire, bayonets, and gas. They were in Hades, and they knew it. And - they knew they were in Hades together.

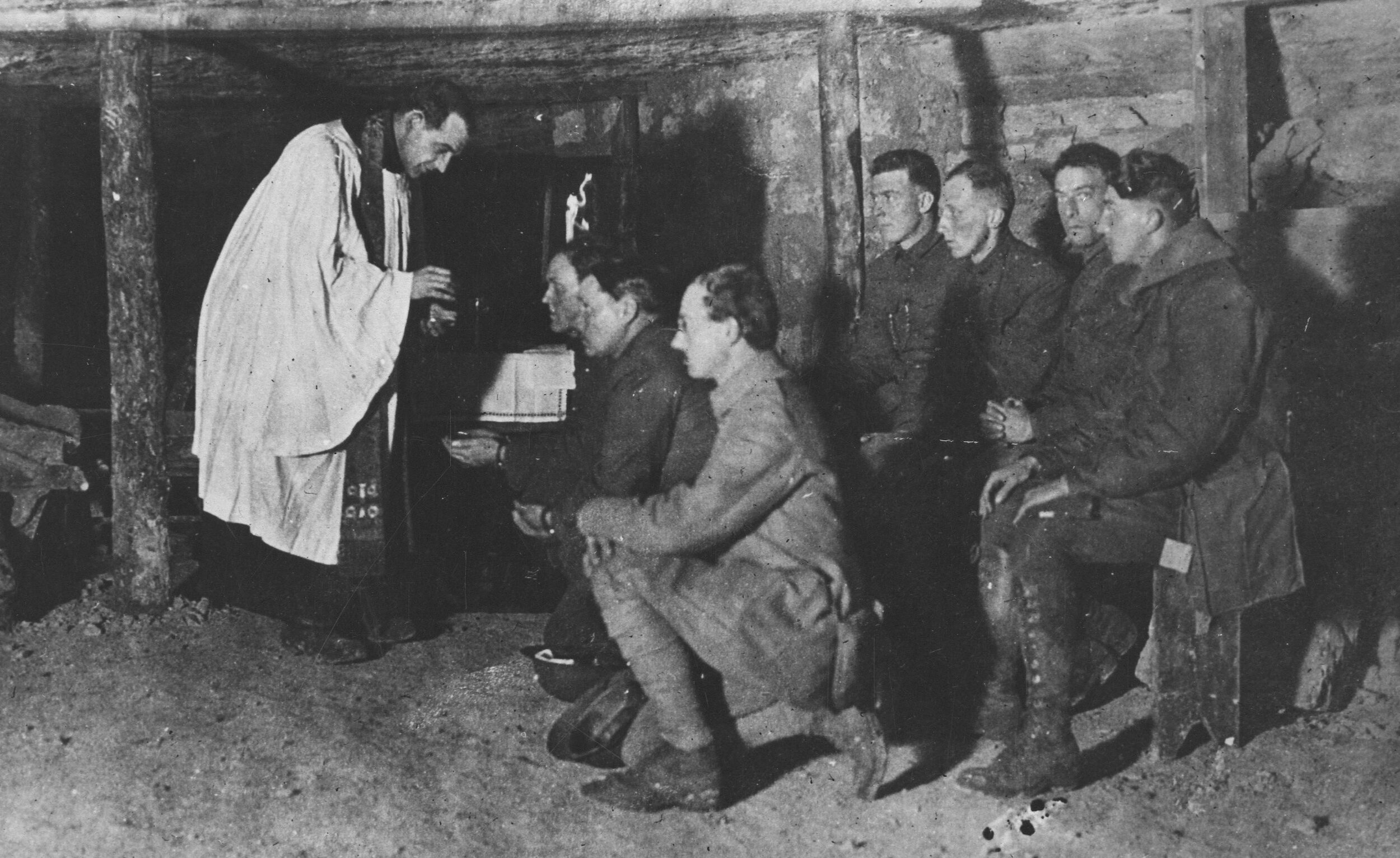

Now the padres: which side of the River Styx were they on? Safe in the Land of the Living with General Alderson, or in the maw of the hellmouth of the salient? Actually the padres could be where they wanted to be. A padre operated with a great deal of autonomy. Literally every other person in the army structure has a place to be in such a situation; they have their various posts. But a padre doesn’t have a post. He’s attached to a Brigade but he’s not within the command structure of that brigade, and he doesn’t have a set place to be at any given time. The attitude of high command, at least at the outset of the war, was that the use - and pretty much the only use - of the padres was to the dead, giving them Christian burials. And if the padres had agreed with that assessment they should certainly not have been in the Salient during the days of April 22-25. They should have stayed West of the Yser Canal. I think that most of the generals would have preferred that. But the padres saw their role differently. Canon Scott wrote, “The whole conception of the position of an army chaplain was undergoing a great and beneficial change…. Chaplains were being looked upon more as parish priests to their battalions.” At the time of the battle, Canon Scott was living on the west side of the canal, and he could very easily have stayed there. He did not. He spent much of the Second Battle of Ypres walking around the salient, fairly aimlessly, like one of the peripatetic bishops of the middle ages. As he encountered soldiers, he would chat with them, comfort the wounded and give them communion – he carried pre-consecrated host around in a little pix, hand out little crucifixes if they wanted them. He gives communion and absolution to dying men. At one point he recrosses the canal to the safer side, in order to visit the 2nd Field Ambulance station, which had been set up in a schoolhouse in the borough of Vlamertinge. The injured have overflowed the schoolhouse so they start using the church as well. Canon Scott is inside this church when he hears the cry of a distressed voice, “O God! Stop it!” “I went over to the man,” he writes. “He was a British sergeant. He would not speak, but I think in his terrible suffering, he meant the exclamation as a kind of prayer. I thought it might help the men to have a talk with them… Then I said, “Boys, let us have a prayer for our comrades up in that roar of battle at the front. When I say the Lord’s Prayer join in with me, but not too loudly as we don’t want to disturb those who are trying to sleep.” I had a short service and they all joined in the Lord’s Prayer. […] After the Lord’s Prayer I pronounced the Benediction, and then I said, “Boys, the curé won’t mind your smoking in the church tonight, so I am going to pass round some cigarettes.” Luckily I had a box of five hundred which had been sent to me by post. These I handed round and lit them. Voices from different parts would say, “May I have one, Sir,?” It was really delightful to feel that a moment’s comfort could be given to men in their condition. A man arrived that night with both his eyes gone, and even he asked for a cigarette. I had to put the cigarette into his mouth and light it for him.”

What about A. W. Woods? After the war, he wrote: “At the second battle of Ypres, I held the communion service in a reserve trench. Men of all religious denominations were represented in the recipients. Then the boche started to shell us.” “The chaos of the front was immeasurable, with conflicting orders, German troops behind Canadian lines, intense barrages and the gas attack which knocked out many of the commanding officers.” That’s all we have from Woods, and it’s pretty thin. But he was there. He was in the salient. And this jibes with another tidbit: throughout the war there were soldiers who wrote letters to Archbishop Matheson with accounts of A. W. Woods carrying wounded men out of trenches. He did not stay away from the front. The questions that are typically asked about war chaplaincy are whether the chaplains were pro-war imperialists, and whether the soldiers were really religious. But these are not the only questions to be asked. Another question seems more pressing: Given that these men were in hell, would we want the church to have representation there or not? When the Yser Canal separates the Land of the Living from the a land that has become Hades, would we want the church to have some presence in Hades, or not? And the answer that I’ve arrived at is yes, I want the church there, as a witness. And a witness in a double sense: There to witness to Christ in hell; and there to witness hell on behalf of the church. A. W. Woods said after the war, “If the padres had failed overseas, it would have meant the failure of Christianity.” And actually he’s right. It would have meant the failure of Christianity in the Salient, in Hades, where it was most needed. And if had failed where it was most needed, then surely that would be a failure everywhere.

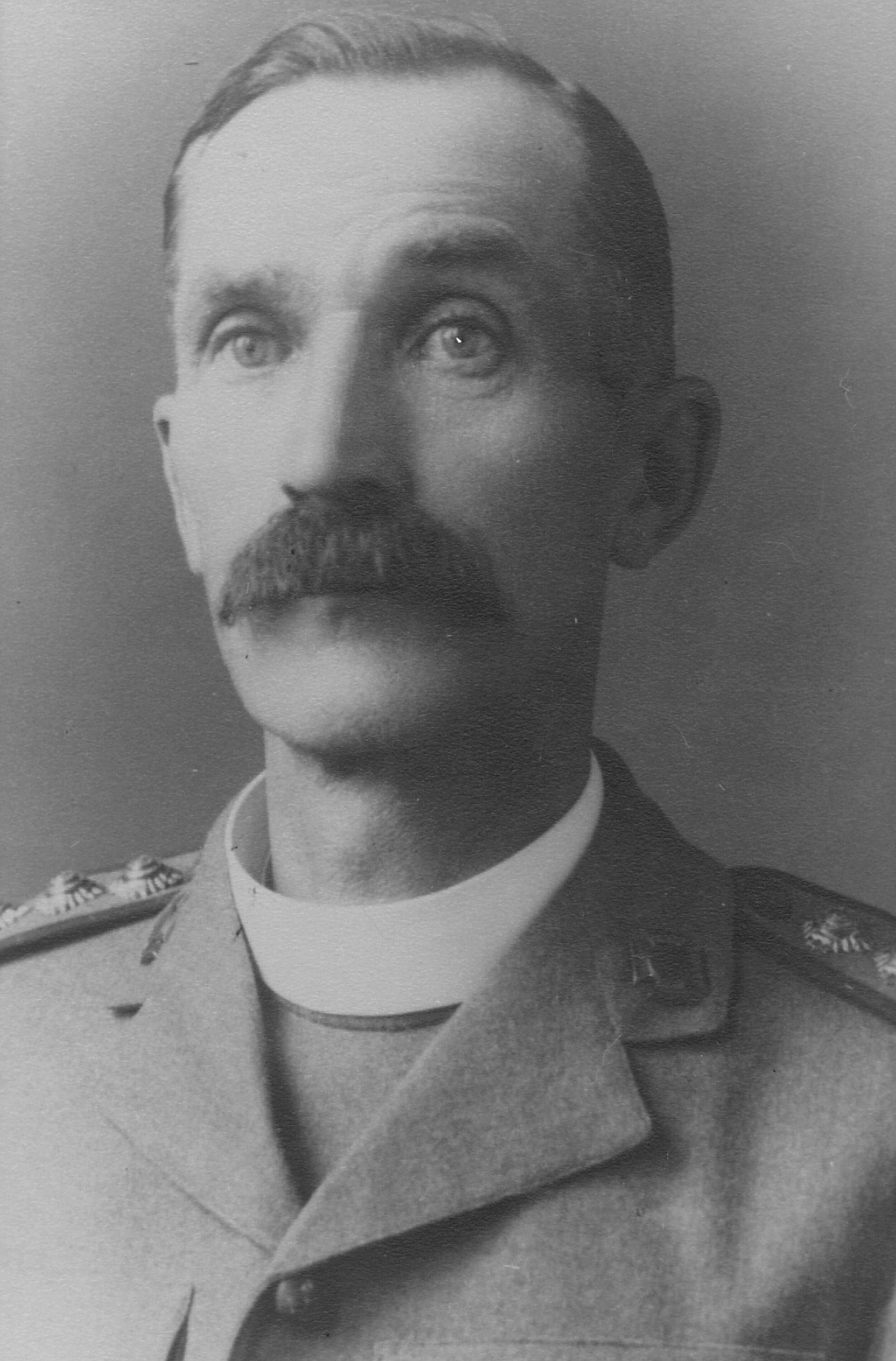

A portrait of A. W. Woods hangs in the back stairwell of St Margaret’s. I always found it disconcerting before - there’s something disturbing about the eyes. But he now looks to me like a man who has been hollowed out from the inside. He resigned his rectorship of St Margaret’s shortly after the war, because his health was “broken by the ravages of gas and trench fever.” His eyes are those of a man who has been to hell.

Another St. Margaret’s parishioner who was gassed at the Second Battle of Ypres is Reginald Minchinton

For an account of what was happening back at the parish, see The Trenches and the Homefront

For more about A. W. Woods’ experience in the war, see: