A. W. Woods: If the padres had failed

PART FIVE IN A SERIES ON SAINT MARGARET’S AND THE GREAT WAR

All of the chaplains’ memoirs that I’ve looked at over the past week express the same acute feeling that they were being put to the test - that the men’s estimation of Christianity depended upon their performance. A. W. Woods put the matter succinctly in 1919, looking back on his time at the front: “If the padres had failed overseas, it would have meant the failure of Christianity.” And it seems that the padres were widely expected to fail, or to at least prove quite useless.

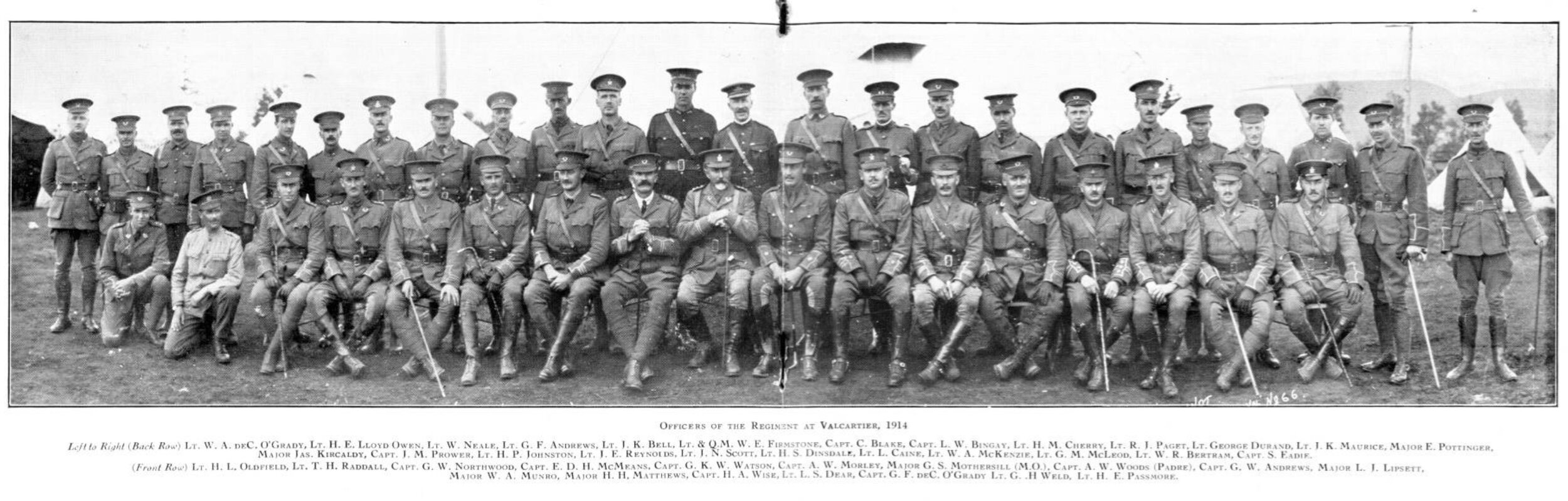

At the outbreak of war, existent local militias across Canada began to mobilize and make their way to the army camp at Valcartier, north of Quebec City, to join the First Division that was being formed and trained there. Most militia regiments had honorary chaplains, and many of these came to Valcartier along with the rest of their regiments. Woods was chaplain to the 90th Winnipeg Rifles Regiment, but had no experience of war. He was 50 years old, a keen rifleman, and fit. George Anderson Wells was incumbent in Minnedosa and he too was an honorary regimental chaplain, to the Fort Garry Horse, and would spend time with them at militia camps in the summer. He was 35 and a veteran of the Boer War. Many such regimental honorary chaplains showed up at Valcartier, “about twenty-five or thirty in all” according to Canon Frederick Scott in The Great War As I Saw It - “we were rather an awkward squad, neither fish, flesh, nor fowl.” The British government (that is, Lord Kitchener) had directed the Canadians to send five chaplains with the First Division. The Canadian Minister of Militia, Sam Hughes, now had five or six times that number on his hands. Wells recounts, “He looked us over and then said, sharply, ‘Do you fellows all expect to go with the First Division?’ With one accord we answered, ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Then,’ he said, ‘some of you are going to be greatly disappointed. Ten of you will go, and not another damn one!’”

So about ten were sent, which meant that there was less than one chaplain per battalion (very roughly 1000 men). Some battalions had chaplains and some didn’t. The British were displeased that their orders had been disobeyed; they had asked for five chaplains and expected five, not ten. In any case among those first ten sent over were Woods, Wells, and Canon Scott. The Winnipeg Rifles militia was formed into the 8th Battalion, and Woods remained its chaplain. Similarly, the Fort Garry Horse was formed into the 6th Battalion, and Wells remained its chaplain. By mid-September they were encamped on Salisbury Plain in the south of England, training for battle. Woods reported to the Senior Chaplain, “Being an expert rifleman I have been able to assist the green shots in some measure.”

A. W. Woods would later speak about the change in attitude among the commanders about the value and role of the padres. “When we started out from Canada in 1914 the chaplains were looked on by army officers as so much more impedimenta, something that had to be carried around, but was of no use. The chaplain had to make good, and he did it. As proof of this fact I cite the words of one lieutenant-colonel, who said, “My chaplain is the most important officer on my staff.” Another proof is that the general of my brigade told me that if the chaplain service was not increased forthwith, he would send me to England to negotiate for that increase, and I would stay there until more chaplains were granted for the brigade.”

And on another occasion, repeating himself a bit: “A word might be said in reference to the attitude of both officers and men toward the army chaplain. It will be remembered that at the beginning of things the chaplain was looked upon as so much unnecessary baggage - to put the matter bluntly - and FIVE per Division were thought to be sufficient… It was seen anyhow that after all the padre was of some use in the army on active service. The officers and men were quick to see that he intended to be one of themselves, and as far as possible play the game. So today we find that every Battalion Commander wants his padre. And no one is more welcome in the trenches than the padre.”

How did the padres so prove themselves? That will be the subject of my next post.