A. W. Woods: Shattered

PART FOUR OF A SERIES ON SAINT MARGARET’S AND THE GREAT WAR

November 10th 1920 - exactly one hundred years ago today - the founding rector of St. Margaret’s, A. W. Woods, submitted his letter of resignation. The wardens called for a special meeting of parishioners for that same evening, and the attendance was large. Woods’ letter was read out to the assembly by the Rector’s Warden, a young teacher at Kelvin named Wallie Mulock. The minutes record that the assembled parishioners accepted the situation only “after several expressions of deep regret that the Rector should have felt compelled to tender his resignation, and having assurance from several members of the parish who have been in close touch with him for some time, that it was impossible to avoid this decision.”

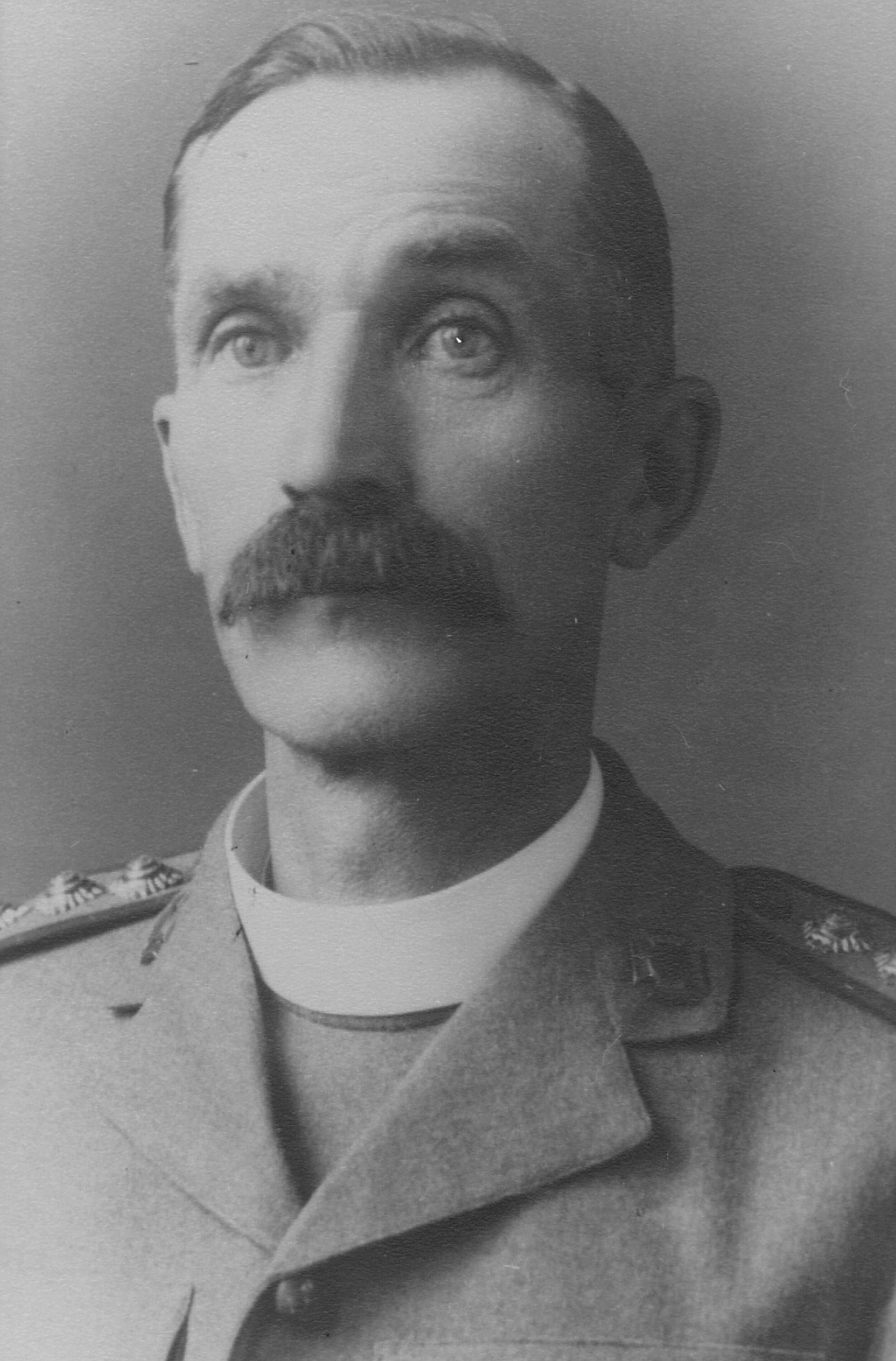

Here is my take on what happened. Albert William Woods was a tremendously energetic man, a man who initiated projects and got them done. His life up until the founding of St. Margaret’s is a succession of missions and projects. But he undertook two great projects in his life - the first was St. Margaret’s and the second was his chaplaincy in the First World War. When he came back from the war, he wanted to continue on with the great project of St. Margaret’s - the building was half built at the time. At 56 he was not exactly elderly. The wardens and congregation had missed him, and waited for his return. He was not just the first rector, he was the founding rector. It was not as if there was an existent parish that received Woods as first rector. It had been his mission. He had door-knocked through the neighbourhood inviting people to a new church plant. It was very much his parish, and I think that the records convey that both he and the parishioners had a strong desire for him to continue. But he found that he simply could not go on. He had truly given everything at the front. The chaplaincy work had been unending, he was not a young man, and he had pushed him relentlessly from 1914 until 1918. Newspaper reports from the time say - and I take this to reflect what was said at that November 10 meeting - that his health was “shattered” by his time at the front, that he, “due to continued ill health, is forced to give up his work in the parish he founded 15 years ago,” that he had returned from the war “broken in health due to the ravages of gas and trench fever.” I take these statements at face value; his health wasn’t just affected, it was shattered and broken. From the time of his retirement and move to Victoria in December 1920 until his death in December 1936 at age 73, there is very little material to be found about A. W. Woods. Prior to 1920 he is mentioned in newspapers very often, giving talks, writing letters, involved in various organizations. In the last 16 years of his life, I think he was so weakened that he just stopped doing stuff. The appointment as Sergeant-at-Arms of the BC Legislature carried with it a decent salary, and I suspect, little actual work.

What I want to do over the next three posts is show what it was that Woods was up to during the war, how he pushed himself far beyond the point of exhaustion, and how he ended up with the effects of gas and trench fever. First though, a glimpse of the how the congregation at St Margaret’s regarded his return. He returned to Winnipeg before the armistice, on what was at least theoretically a three-month furlough beginning in September 1918. The armistice was declared before his furlough was over, and he was discharged. The Free Press described his reception at the train station in September.

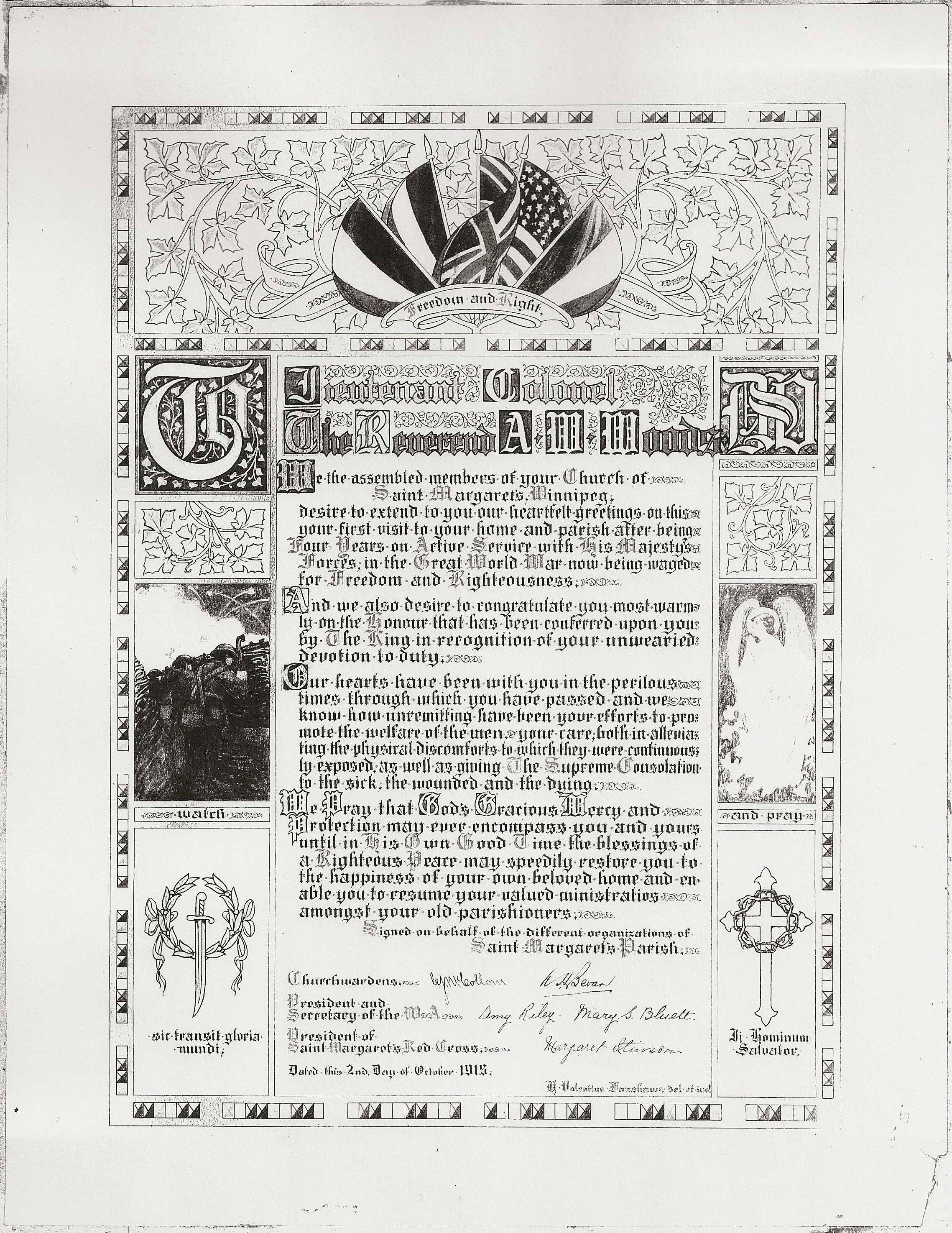

“As Col. Woods descended the steps from the train platform he was greeted with cheers and soon surrounded by a host of friends. It was some minutes before he could make any progress toward the exit, outside of which a number of autos were parked, and and as he made his appearance, there was a continuous tooting of auto horns and great cheering. The greeting was an ovation enthusiastic and affectionate, and the rector was escorted to his home by a procession of automobiles. ‘The trip across was fine,’ said Col. Woods, ‘and I am glad to be again at home.’ It was impossible to retain the chaplain in conversation, as his friends gathered around him to extend their welcome and greetings.” The parish had arranged for an illuminated address to be made by a parishioner, Valentine Fanshaw (see “A Manifest Presence” p. 25), thanking him for his “unwearied devotion.” “We know how unremitting have been your efforts to promote the welfare of the men in your care both in alleviating their physical discomforts as well as giving The Supreme Consolation to the sick, the wounded, and the dying.” The great esteem in which A. W. Woods was held, not only in Winnipeg but within the military, is also shown by the fact that he is one of only seven chaplains from the Great War (out of 524) to be awarded the Distinguished Service Order. When the local board of the Repatriation Commission (which would help the men reintegrate into society, find training and employment, etc) was set up in December 1918, “Lieut.-Col. A. W. Woods was the unanimous choice as honorary chaplain.”

But back to the special meeting of parishioners, November 10, 1920. The parish reluctantly came to accept that Woods’ health really would not permit him to continue. Who was to replace him? Woods had a suggestion, a fellow Senior Chaplain from the war named George Wells. His wardens were amenable to the idea, and the assembled parishioners passed a unanimous motion to petition Archbishop Matheson to invite Wells to be the next rector, which is what indeed happened. As Senior Chaplains to Divisions (Woods the 3rd, Wells the 2nd), Woods and Wells were each responsible for the spiritual care of about one quarter of the soldiers in the Canadian Corps, which had four divisions. So the fact that Wells succeeded Woods as rector leads to the rather remarkable situation that for much of the second half of the war, something like half of the Canadian soldiers on the Western Front were under the spiritual care of one or the other of the first two rectors of St Margaret’s. George Anderson Wells would go on to become the warden of St. John’s College, Bishop of Cariboo (Interior BC), and then in the Second World War he set up and ran the chaplaincy services for the Canadian Forces, ending up an honorary Brigadier, “the Fighting Bishop,” and the most highly decorated chaplain in the history of the British Commonwealth.

A. W. Woods preached his farewell sermon at St. Margaret’s on Dec 26, 1920. The Free Press reported that he would be “greatly missed by the congregation, and by all who knew him.”

-GM